Should you shoot in RAW- or JPG-format? Or TIFF? Or something completely different?

I know that a great deal has been said and written on this subject already. And I know that it pops up daily on discussion forums, in magazines on web sites and in talks between photographers.

So this little article is just another brick in the wall.

But I'm gonna lay it down anyway and tell you why I'm a RAW-shooter.

Why it's interesting

The format talk is interesting because your choice of file format in the camera and the settings for the selected format can have a significant influence on the quality of your final images. The selected format can also influence the performance of your camera and the time spent at the computer afterwards.

Some formats are slower to handle in the camera's processor or may create larger files, which all has influence on how many pictures you can store on a memory card and how fast they can be saved.

For the larger part of photographers it's the quality issue that is the most important.

For a smaller fraction the speed issue is important -- frames per second really counts for some.

Let me tell you what I do and then just sketch briefly what the different formats are and what they can do in terms of quality.

My recommendations

My personal recommendations are that you always shoot RAW. This format keeps all the captured information intact and will preserve your shots best. This is my personal preference. Others think differently.

If you need a more speedy workflow and want to avoid the conversion process, shoot RAW+JPG, and select the best quality, highest resolution JPG that your camera supports -- or at least a bit higher than you need it. Work on the JPG's, and find comfort in the fact that you have an even better copy stashed in your RAW-file.

And please don't start whining about too little space on the memory card or in the computer! Buy some more and some bigger cards. Memory cards are very inexpensive these days, as are large hard drives for your computer. Prices are also constantly dropping, so stock up on storage, and always buy bigger than you need -- much bigger!

The only place I personally feel that the large number of bulky files are a menace, is when I copy from card to computer. That can also be remedied by using high speed units such as USB-2 or FireWire cables and/or card adapters.

Ken likes JPG

Ken Rockewell is a photographer who writes a great deal ebout photography online. He shoots JPG exclusively and his arguments for doing so are:

- The quality is the same (I don't agree)

- The workload is too high (I partly agree - more work more quality)

- The disk space consumed is not worth is (I don't agree. Scrapping your RAW's is like scrapping negatives or slides, only keeping the scans)

Ken can think what he will - I buy some more hard disks.

[Dynax 7D, Sigma 15mm f2.8 fisheye]

Your digital negatives

The files that you pull out of your camera are comparable to your negatives or your original slides. You must guard them with all your might! Once they are gone, there is no way of coming back to the original image. Not even if you have the images displayed on the web, have converted for printing or have high-rez prints available. These copies will only rarely contain the same level of details as the originals.

The better the originals are, the better copies you can make, and RAW provides the best originals. They contain the untouched dump of what your sensor recorded when you pressed the release button.

So save your RAW files, write protect them, burn them on DVD's and stream them to external disks, so that you can preserve them for eternity. Or at least for a long time...

By keeping the RAW-file you get another advantage: when you get access to better conversion-technology or simply get better at mastering the process yourself, you can re-convert your pictures and get even better results. Once the conversion has taken place in the camera, the RAW-file is trashed if you shoot JPG only. There is no chance of later using different or better algorithms. Add to that that camera algorithms are optimized for speed, not for quality.

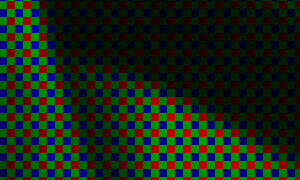

At 800% each pixel, representing a sensor dot, is visible as a red, green or blue square.

Click to see full sample.

RAW - untouched

The RAW file format is exactly what is says: raw. It is in essence a raw dump of what the sensor has captured. Look at the picture to the right. This is actually an unconverted RAW-image. Or rather a very small part of a RAW-image. The original was shot with a Minolta Dynax 7D, and was 2000 by 3008 pixels large. This small sample is just some hundred pixels on each side and has been significantly enlarged. You can see even more of the sample by clicking on it.

As you can see, it is not even close to looking any good. You might recognize the pattern. It is an RGB-pattern, consisting of Red, Green and Blue pixels (actually 25% Reds, 50% Greens and 25% Blues, but that's another and more complicated story). Each pixel has a certain level of intensity, and combined in the right way, these pixels form "real" pixels with "real" colors. The combination can be done in different ways, and that's what the RAW-converter does -- in the camera or on your computer. It produces an image with the right colors rather than red, green and blue dots.

The RAW-file is the digital negative, in the meaning that is has the maximum amount of the information that was captured when the shutter opened. It is not modified in any way, so there is no effect from white balance settings, no sharpening and no change in color saturation or anything. And that is no matter how your camera settings were. The camera registers the information from the sensor, pixel by pixel and saves the whole sherbang in the RAW-file.

If anything has to be done to the picture with regards to color changes, sharpness etc. it has to be done in the converting process or afterwards in the post-processing.

Click to see full sample.

TIFF - converted - saved without loss

The TIFF-format is not used that much any more. Only a few cameras can produce TIFF's directly, but they are still interesting for understanding the process because the TIFF file has an interesting trait: it retains all the "real color" pixels exactly as they were. Why that is interesting will become obvious in the next chapter, but for now I will just let you know, that a TIFF-image is exactly as the converted RAW-image. Opposite the RAW-image, you can actually use the TIFF to look at. In this stage the image is naturally colored. All cameras convert from RAW and store their pictures in a TIFF-like format internally before writing a JPG-file on the memory card or embedding it in the RAW-file or as a thumbprint.

It has all the details that the original had and will have so no matter how many times you open and save it if you keep on using the TIFF file format or some similar lossless format. You will only loose information from the original when you work on the image, like when you rotate, scale, run filters on it or perform other editing tasks. And if you save it in JPG.

Other formats like Photoshop's PSD-format have the same ability. They keep the picture as perfect as possible. The price is file size. The files are typically large.

The naked eye will usually not be able to see the deterioration, but this 800% enlargement shows it clearly.

Click to see full sample.

JPG - converted - saved with loss

The file size is exactly what the JPG-format handles so well. JPG's primary virtue is it's ability to compress the image and save space. That can be interesting when you save pictures to the memory card in your camera -- or post them on the web. You will notice that the same memory card will contain many more JPG- than RAW-pictures.

The natural conclusion would of course be to use JPG all the time, were it not for one thing: JPG is a so-called lossy file format. One of the ways that the JPG-software manages to squeeze the image smaller in file size is by throwing away details. I will not explain this in details, but just illustrate it with a simplified example. The JPG-system splits the image into some squares, a few pixels on each side. These squares are not saved as individual pixels, but with some descriptive information that may take up less space than the original pixels. It's pretty complex math involving discrete cosine functions, quantization, Huffman coding and other kinds of voodoo, but the net result is that some subtle details are lost.

The loss is usually invisible to the naked eye, but it is there, and once the original is saved in JPG, detail from the capture has been lost forever.

On top of that, opening and saving JPG-images will add further to the loss, since the software will now try to do the trick once more on the already modified image.

RAW-conversion

The subject of RAW-conversion deserves a whole article in itself -- or maybe even several. For now I have just touched on the format and some of the RAW-programs I have tried. I will return with more on this interesting part of the digital photography process.

OK now, what should you use?

As I already wrote: use RAW if you can. I know a lot of photographers will recommend JPG only, and they are of course entitled to their opinion and have their reasons for doing so.

I personally do not want to compromise the image quality and want to be able to draw as much information from my images as possible. And the RAW-files represent the richest possible version of my digital images. The RAW-files will contain all the details that the sensor sensed, and I will usually be able to pull out more details from highlights and shadows, get better colors and get sharper details from a RAW-image.

If you aren't as picky as I am with preserving quality, you can opt for a good JPG-format. Many photographers do so and are happy with that. I also do that by shooting RAW and JPG at the same time, and usually work on the JPG's for quick results, but always have the RAW to return to for even more details and more manipulation potential.

Years later

A friend of mine used to shoot with a D70. He always shoots RAW and has all his raw files saved from back when he started shooting digital. Recently he worked his way through a bunch of these RAW-files using the latest incarnation of the Danish Phase One RAW-converter, and with this new and updated converter combined with his improved knowledge of convterting he could produce images that were a lot better than the JPG's he had made back then.

This illustrates my point very well: your taste, your knowledge, your skills and the technology you use can get much better over the years, and by having the pictures you took stored pixel by pixel as the sensor saw them, you can improve the quality of the same pictures years after you shot them.

Links

Photo.net has a very in-depth and technical article on JPG-compression.